Samu

- Shinjin

- Aug 25, 2022

- 0 min read

What is Samu?

Traditionally Samu (作務) is participation in the physical work needed to maintain the Zen monastery. According to tradition, it was emphasized by Baizhang Huaihai, who is credited with establishing an early set of rules for Chan (Chinese Zen) monastic discipline, the Pure Rules of Baizhang. As the Zen monks farmed, it helped them to survive the third wave of the Great Anti-Buddhism Persecution (845AD), more than other sects which relied more on donations given whilst "begging" during Takuhatsu. The rules of Chan are still used today in many Zen monasteries. From this text comes the well-known saying "A day without work is a day without food" (一日不做一日不食 "One day not work, one day not eat"). Now that might be a little extreme by Western standards, but it does show how important mindful work is in Ch’an/Zen practice. Samu is also written as Samou. Samue (作務衣) is the work clothing of Japanese Buddhist monks, worn when engaged in samu.

In Zen Buddhism today, great importance is still placed on working for the community. Such work is done in the spirit of generosity and devotion. The collective energy of practising Zen Buddhists still allows for the founding of numerous dojos and monasteries. Samu is essential for the daily workings of such establishments. Cooking, cleaning the premises, preparing bouquets of flowers for the alters... all of these tasks are carried out in the spirit of generosity - a core value of Buddhism. During sesshins - meditation retreats - time is devoted to samu, allowing participants to work in concentration and silence, one step at a time. It is a way of carrying zazen (meditation) off the zafu (cushion): with the simple act of performing duties with a complete concentration of body and mind, life becomes simple and serene. "Chop wood, carry water".

However, as a member of an online sangha, there is no such physical functionality and community to support. The Sangha is virtual, and yet we do support one another as we can. We also support ourselves and our families with the daily running of our households - washing the pots, financial matters, cleaning the toilet, and making the bed are all forms of samu. As was the logo design and website building that I did for the Sangha.

Similarly, the work and activities we do in the communities we touch can be Samu.

Samu, the Noble Eight Fold Path and the Mindful Dharma of life

As with much of Buddhism, Samu is not so much the work, but rather the mental discipline of doing this one thing in front of us, in this moment, to support the community.

It ties in with the Noble Eightfold Path - "right" view, "right" intention, "right" speech, "right" action, "right" livelihood "right" effort, "right" mindfulness, "right" concentration - where right is the guidance towards nurturing the spirit of awakening: something very similar to the spirit of altruism. Altruism is when we act to promote someone else's welfare, even at a risk or cost to ourselves; here we do not have to risk ourselves nor take a cost we can not endure - and yet we should feel a "pinch" of true giving.

Early canonical texts state right livelihood is avoiding and abstaining from wrong livelihood. The virtue is further explained as "living from begging, but not accepting everything and not possessing more than is strictly necessary". We can see that Chan/Zen came to an understanding that there was a need to be monastically self-sustaining during the Four Buddhist Persecutions in China. When we have practised and learnt of Zen to a point that it is just part of what we "do", we are mindful of "right" where there is less comparison, which is at the heart of dissatisfaction.

Whether we are comparing what is to what isn’t, whether I am comparing my current self to a past self or an ideal self, comparing the present to the past or the future, dissatisfaction always stems from duality. It stems from, “I am,” and, “I’m not.” It stems from “want,” and, “don’t want.”

It blinds us to the majesty of life with, “have,” and, “have not.”

Mindfulness involves returning to our senses and immersing ourselves in the present moment rather than our ideas and feelings about the present moment. It involves us acknowledging/awakening to the fact that we spend a lot of our time dreaming! Our twice-daily practice of Zazen is where we return to this; to solely meditate/self-medicate the dis-ease of our suffering. Purely just returning to the moment and training ourselves to experience that as it is. Perhaps using the labelling technique of any arising ideas or thoughts as 'pleasant', 'unpleasant', 'mixed', or 'neutral', to ease us into equanimity. To carry that calm awareness and response to our feelings and thoughts will always be practised until it is more natural than it was the moment before.

Can the mind be full of equanimity?

When we usually think about mindfulness, we think of nice nature walks, swimming or riding a roller coaster Yet reserving mindfulness for idyllic situations misses the mark.

Mindfulness is a constant practice. How present are we with this moment?

It is not so much a case of; “Oh, this is a great time to be mindful!” As a Zen student, if you aren’t sitting zazen, then you have the opportunity to practice mindfulness. Discipline sees that there isn't opportunity: it is a state of being.

Dogen said that there is no Dharma apart from ordinary life. Ordinary life involves work, and thoughts and feelings about what we encounter. How we endure unpleasantness often has to do with our pre-programming.

We have to clean the house, mow the lawn, pull the weeds, make lunch for the kids and labour for eight hours at an office, store or factory. Samu! Samu! Samu!

Without samu, four unenjoyable moods arise - anxiety, self-blame, depression and difficulty in emotional regulation. Often we label these collectively as stress and boredom.

We don’t necessarily need to quit our jobs or medicate ourselves to remedy these states of mind. The problem isn’t what we’re doing. The dissatisfaction/suffering is our mental state of wanting to be somewhere else, doing something else.

By working with mindfulness, we can abide with what is and do what needs to be done, all the while, a smile is waiting to float to the surface; a laugh is waiting to bellow out from the belly. Generally, there are things we can find to enjoy, even in some of the things we might initially think of as unpleasant.

We don't tend to enjoy "sucking it up" here in the West; where we are often taught to seek quick satisfaction either by ceasing that which causes us unhappiness or distracting ourselves from it - gaming, tv, or even complaining. If we can just be with the job at hand, and experience it, separate from the projections of self would it have been both easier and more rewarding?

Performing a necessary service for people. How can that be unfulfilling?

Is it because we live mindlessly that our time here is unenjoyable and unfulfilling?

- When I am cleaning is my approach to it as an experience, that of 'unpleasant' and a 'be-grudging' to the time required to complete a chore that is 'expected of me'? - If I am "dreaming"ly approaching the task of cleaning, this one thing, with the mind full of those judgments, do I miss the opportunity to appreciate the smooth figure eight motions of waxing a wooden floor and marvelling at how it glimmered in the fluorescent lights?

- Is it because I was mindless that I found no joy in helping customers find what they needed to nourish themselves? - If I can 'ground' myself in the moment and experience the smell of the cleaning products, the flow of the pen on the paper, the sound of the keyboard clacking, the sight of sunlight through the leaves - can I say that I enjoyed something about the 'unpleasant' job at hand? - and was it, therefore, the totally unpleasant experience that I was projecting on the future? or was it a series of 'mixed' ideas, thoughts and feelings that I gently held, rather than tightly grasping the one 'unpleasant'? Again labelling any arising ideas or thoughts during the activity as 'pleasant', 'unpleasant', 'mixed', or 'neutral', eases us into equanimity. We are training ourselves towards a different way of responding to stimuli than we have turned to in the past. With zazen and samu we train ourselves to abide with the harder aspects of life.

Pacing, Samu and Tarot

My physiotherapist said, "Learn to dance with the pain".

- In 2015 I was baffled even by her explanation of this. Over the years I have come to understand that what she meant was to come to a place where you can hear what you need.

It is vital that we "put on our own oxygen mask before helping others", if we do not have the energy to give we can not give it.

Our mental and physical health manifest not only in our personal health matters but in our approaches to the tasks we have to complete for ourselves and others.

Zazen and samu are training disciplines that can also fall by the wayside when we are unwell.

Again, I have come to the conclusion that if I don't at least take a number of sacred pauses throughout the day - 3 breaths to connect with myself, to hear myself - then I can't attend to my own ebbing energy or frustration levels.

In the sangha that I belong to we practice zazen for a maximum of 20/25 minutes. So I came to the understanding that if I was dancing with the pain/dis-ease that might arise during that and abiding with say the pain in a joint, or an itch for a while before moving slightly or completely. Then so it is with life and its tasks. 15 - 25 minutes of focus, and then a break still builds towards forwards momentum. Who said there was any real difference between the hare and the tortoise? They both finish the race, right? Did the hare take a nap because, as we are taught, he was arrogant, or did he need it? Did the tortoise plod along but miss the experience of each step, was he frustrated by his pace at all? Who is to say?

Toiling mindlessly, through eight-hour working days, transforms them into eternity. Whereas those eight hours go by in a blink when I'm at home doing what I want to do. Want = desire; a thief that is always ready to steal away the experience of this moment.

Want always appears with its sibling - don’t want. If I want to be at home, that means I don’t want to be at work. If I want to relax in front of the TV, that means I don’t want to do the dishes. All this = resistance to what actually is

What if there is a Middle Way?

Mindfulness helps us ease our tight grip on want and don’t want. Or it allows us to at least integrate want and don’t want into the present moment as barely audible background noise. Attachment and aversion are like tinnitus; rambling away in the distance without obscuring other sounds.

My attachments and aversions are irrelevant. My comparisons and categories are irrelevant. My remembered past and imagined future are irrelevant.

This is equanimity = "calmness and composure, especially in a difficult situation" = abiding with the moment as it is.

What is relevant is right here and right now; casting aside my arbitrary barriers and categories and immersing myself in the present moment. Because the present moment is all we ever have. I have no past, I only have memories. I have no future, I only have dreams. The present moment is all there ever is, so right now is the only time I can ever uncover the peace and happiness that is always available to me.

- No one says I can't take a pause, IN FACT, ITS ENCOURAGED!

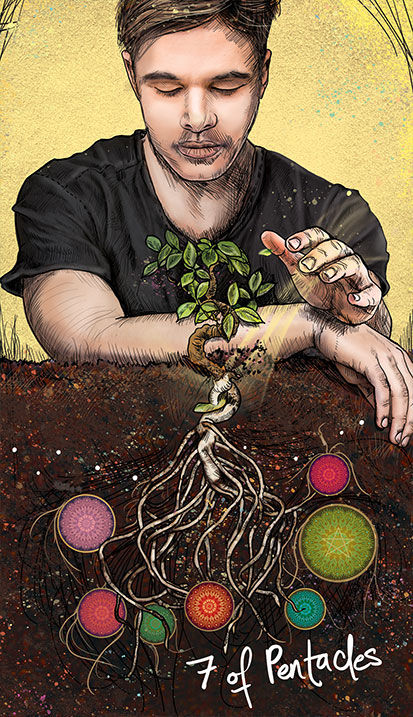

^ Image from the Lightseers Tarot by Chris-Anne

In her poem The Seven of Pentacles, Marge Piercy writes:

"Under a sky the colour of pea soup,

she is looking at her work growing away there,

actively, thickly like grapevines or pole beans,

as things grow in the real world, slowly enough.

If you tend them properly, if you mulch, if you water,

if you provide birds that eat insects a home and winter food,

if the sun shines and you pick off caterpillars,

if the praying mantis comes and the ladybugs and the bees,

then the plants flourish but at their own internal clock." - sometimes in life, we have to just let the seeds grow. To constantly tend to them doesn't appreciate the stage it is at. To disturb the soil to peek at the germinating seed would only be to jeopardise the possibility. Like Schrödinger's cat! = In quantum mechanics, Schrödinger's cat is a thought experiment that illustrates a paradox of quantum superposition. In the thought experiment, a hypothetical cat may be considered simultaneously both alive and dead as a result of its fate being linked to a random subatomic event that may or may not occur. If my happiness is affected by where I’m at or what I’m doing, then it isn’t real happiness. Happiness, perhaps like Schrödinger's cat, exists regardless. It and peace are what I grant myself.

True intimacy and Mindfulness

In Zen, anything that’s dependent and constantly changing is unreal and insubstantial. It’s by becoming intimate with the present moment, by engaging things as they are, that I uncover real happiness and real satisfaction. So if I can’t be mindful and grateful for what I’m doing and where I’m at right now, how can I ever be truly happy anywhere else?

Happiness derived from escapism is fleeting. Because there’s always more work to do, always more sweat to sweat. Yet when work becomes samu, each bead of sweat is savoured. Time becomes just another idea to see through and every moment is an opportunity to laugh.

We are never more ourselves than when we’re laughing. Samu! Samu! Samu!

Comments